The JFK 100

JFK and the CIA

Were the President's own officers conspiring against him?

Were the President's own officers conspiring against him?

Author Gus Russo has a very different perspective on JFK's relationship to the Central Intelligence Agency, as well as the President's personal relationships with top CIA officials like Allen Dulles. And unlike the claims of L. Fletcher Prouty, Russo's conclusions are based firmly upon the documentary record, not anecdotal evidence and speculation.FLASHBACK TO the Pentagon offices on a day in 1961. A document is moved by hand into Lemnitzer's office where we see a set of hands holding it while it's read. There's a look of surprise on Lemnitzer's face.X I was a soldier, Mr. Garrison. Two wars. I was one of those secret guys in the Pentagon that supplies the military hardware -- the planes, bullets, rifles -- for what we call "black operations" -- "black ops" -- assassinations, coup d'etats, rigging elections, propoganda, psych warfare and so forth. World War II -- Rumania, Greece, Yugoslavia, I helped take the Nazi intelligence apparatus out to help us fight the Communists. Italy '48 stealing elections, France '49 breaking strikes -- we overthrew Quirino in the Philippines, Arbenz in Guatemala, Mossadegh in Iran. Vietnam in '54, Indonesia '58, Tibet '59 we got the Dalai Lama out -- we were good, very good. Then we got into the Cuban thing. Not so good. Set up all the bases for the invasion supposed to take place in October '62. Khrushchev sent the missiles to resist the invasion, Kennedy refused to invade and we were standing out there with our dicks in the wind. Lot of pissed-off people, Mr. Garrison, you understand? I'll come to that later . . . I spent much of September '63 working on the Kennedy plan for getting all US personnel out of Vietnam by the end of '65. This plan was one of the strongest and most important papers issued from the Kennedy White House. Our first 1,000 troops were ordered home for Christmas. Tensions were high. . . .I never thought things were the same after [the JFK assassination]. Vietnam started for real. There was an air of, I don't know, make-believe in the Pentagon and the CIA. Those of us who'd been in secret ops since the beginning knew the Warren Commission was fiction, but there was something . . . deeper, uglier. And I knew Allen Dulles very well. I briefed him many a time in his house. . . . But for the life of me I still can't figure out why Dulles was appointed to investigate Kennedy's death. The man who had fired him. . . .

You know in '61 right after the Bay of Pigs -- very few people know about this -- I participated in drawing up National Security Action Memos 55, 56, and 57. These are crucial documents, classified top secret, but basically in them Kennedy instructs General Lemnitzer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, that from here on forward . . .

X (VOICE OVER) (CONT'D) . . . the Joint Chiefs of Staff would be wholly responsible for all covert paramilitary action in peacetime. This basically ended the reign of the CIA -- "splintered it," as JFK promised he would, into a "thousand pieces" -- and now was ordering the military to help. This was unprecedented. I can't tell you the shock waves this sent along the corridors of power in Washington. This and, of course, firing Allen Dulles, Richard Bissell, and General Charles Cabell, all of them sacred cows of Intell since World War II. You got some very upset people here.

Russo writes:

The Kennedy brothers had . . . preserved a long-lasting association with Allen Dulles, then CIA Director. Letters in both the Kennedy and Dulles collections reflect that John and Robert Kennedy maintained correspondence with both Dulles brothers from at least 1955. Traveling in the same social sphere, Allen Dulles and John Kennedy were "comfortable with one another and there was a lot of mutual respect," Richard Bissell said in an interview. In fact, Kennedy was known to regard Dulles as a legendary figure. Historian Herbert Parmet wrote, "Dulles often went to the Charles Wrightsman estate near Joe Kennedy's Palm Beach House. As far back as Jack's early days, they socialized down in Florida, much of the time swimming and playing golf." Dulles himself said, "I knew Joe quite well from the days when he was head of the Securities and Exchange Commission." . . .Dulles first met Jack Kennedy at the Kennedy Florida compound in 1955. They became fast friends. "Our contact was fairly continuous," Dulles later said. "When [JFK] was in Palm Beach, we always got together." Jack came to revere both Dulles' intellect and accomplishments.

Robert Kennedy, too, was clearly impressed with Dulles. Regarding his performance at the time of the Bay of Pigs, Robert Kennedy later recalled, "Allen Dulles handled himself awfully well, with a great deal of dignity, and never attempted to shift the blame. The President was very fond of him, as I was." He elaborated to historian Arthur Schlesinger, "He [JFK] liked him [Dulles] -- thought he was a real gentleman, handled himself well. There were obviously so many mistakes made at the time of the Bay of Pigs that it wasn't appropriate that he should stay on. And he always took the blame. He was a real gentleman. JFK thought very highly of him."

Dulles kept a variety of Kennedy secrets from the public. For example, when John Kennedy won the election in November 1960, the CIA under Dulles conducted a background investigation of Kennedy in anticipation of his first intelligence briefing as President-elect on November 18. Such investigations were designed to predict how the subject would respond when informed of the full range of CIA operations, and to show Dulles the most effective method of appeal. Prepared by CIA psychologists, the study included hot evidence from the FBI: the indiscretion of a youthful Jack Kennedy, at the height of World War II, with alleged Nazi spy Inga Arvad Fejos. In 1942, while serving in the Office of Naval Intelligence in Washington, Jack Kennedy had established this potentially dangerous liaison. The FBI, which had wiretapped Arvad, initially compiled the file. Historian Thomas Reeves wrote:

(FBI sources state that it was Hoover's direct pressure that brought about the transfer. The potential value of this kind of political dynamite was most assuredly never lost on the FBI Director. It was just the kind of file that kept Hoover's power inviolate for so long.)When Jack's relationship with the woman became known to Navy officials, the assistant director of the Office of Naval Intelligence wanted to cashier the young ensign from the Navy. A witness remembered the officer being "really frantic." Reminded of Joe Kennedy's prestige, however, the official eventually calmed down and consented merely to give Jack a speedy transfer to an ONI outpost in Charleston, South Carolina.

Dulles' decision, or favor, to keep this matter secret was quite possibly rewarded later, when Kennedy, as president-elect, retained Dulles as CIA Director. It may also have played a part in Kennedy's initial refusal to accept Dulles' resignation after the Bay of Pigs fiasco.

The CIA after the Bay of Pigs

"In the course of the past few months I have had occasion to again observe the extraordinary accomplishments of our intelligence community, and I have been singularly impressed with the overall professional excellence, selfless devotion to duty, resourcefulness and initiative manifested in the work of this group."After thinking it over, it was clear to John Kennedy that the blame for the Bay of Pigs was largely his and not the CIA's. And although Kennedy needed public scapegoats in his administration, he drew the line at a public indictment of the original Eisenhower-era planners of the invasion. Kennedy's Secretary of State, Dean Rusk, later testified, "President Kennedy was very angry when some people around him tried to share responsibility with President Eisenhower because President Kennedy knew that he and his senior advisors had a chance to look at that and made their own judgment on that, and he did not like the idea of having to share the buck."

-- President Kennedy, in a letter of commendation to new CIA Director John McCone, January 9, 1963

Although Kennedy's threat to "splinter the CIA into a thousand pieces and cast it to the winds" has long been used to support theories that the CIA had reason to hate JFK, just the opposite is true. Kennedy's "threat" was a knee-jerk reaction to the failed invasion. Years later, E. Howard Hunt, the CIA's liaison to the Cuban exiles, surmised, "For him [Kennedy] to have said that was probably a way of disguising from himself the fact that he himself was responsible for the fiasco, and I'm sure that's something that haunted him for the rest of his days."

All of John Kennedy's other statements regarding the CIA were nothing short of glowing. On November 28, 1961 Kennedy went to Langley, Virginia to dedicate the CIA's new headquarters, which came to fruition under the out-going Director, Allen Dulles. Addressing the large throng, Kennedy said:

I want, first of all, to express my appreciation to you all for the opportunity of this ceremony to tell you how grateful we are in the government and in the country for the services that the personnel of this Agency render to the country. It is not always easy. Your successes are unheralded -- your failures are trumpeted. I sometimes have that same feeling myself. But I am sure you realize how important is your work, how essential it is -- and, in the long sweep of history, how significant your efforts will be judged.

In addition to the dedication, Kennedy had planned a surprise for his loyal friend. Dulles' biographer, Peter Grose, described the event:

Turning to address Dulles, Kennedy said, "I want to express my appreciation to you now, and I am confident that in the future you will continue to merit the appreciation of our country, as you have in the past." The next day; JFK dashed off a letter expressing his great admiration and affection for Dulles. In closing, Kennedy wrote, "You leave behind you, as witness to your great service, an outstanding staff of men and women trained to the nation's service in the field of intelligence." In what appears to be a genuinely heartfelt letter to his old friend Dulles, the President added, "I am sure you know you carry with you the admiration and affection of all of us who have served with you. I am glad to be counted among the seven Presidents in whose administrations you have worked, and I am also glad that we shall continue to have your help and counsel. . . . Your integrity, energy, and understanding will be a lasting example to all." Two years later, in the wake of JFK's assassination, Dulles' kinship with John Kennedy would play a role in Dulles' decision to withhold critical information from his fellow Warren Commission members.Allen greeted the presidential helicopter at the landing pad hidden among the trees of the campus. Interrupting the carefully scripted ceremony that followed, with more than six hundred CIA professionals in attendance, Kennedy turned to the dais behind him. "Would you step forward, Allen." On his lapel he pinned the National Security Medal. Short of knighthood or lordship, it was the highest honor of the United States government.

On March 1, 1962, JFK would similarly honor Bissell with the same National Security medal. In ceremonies at the White House, Kennedy made it clear that he still held Bissell in high esteem. In part, Kennedy said:

During his more than twenty years of service with the United States government, he has invested a rich fund of scholarship and vision. He has brought about returns of direct and major benefit to our country. In an area demanding the creation and application of highly technical and sophisticated intelligence techniques, he has blended theory and practice in a manner unparalleled in the intelligence profession. Mr. Bissell's high purpose, unbounded energy, and unswerving devotion to duty are benchmarks in the intelligence service.

The Kennedys and the CIA

After the Bay of Pigs, as both he and his brother Robert began to understand the intended role of the CIA, John Kennedy would oversee one of the greatest budget increases for the intelligence community in US history. "You have to always bear in mind how the Agency was originally set up," instructs one high-ranking Agency official. The CIA, he reminds us, was instituted as the intelligence arm of the Executive branch -- the President and official Washington have never been confused about that fact. First conceived by President Harry S. Truman, the CIA was established and organized by the National Security Act of 1947 (Truman submitted it to Congress, which passed it on July 26, 1947).

The CIA's charter is unambiguous in stating that the Agency would function only in response to directives of the President and of the President's own intelligence apparatus, the National Security Council. Nowhere in the charter is there any inference that the CIA would be allowed to initiate policy. JFK, a close student of history, was undoubtedly aware of the Eisenhower-CIA partnership that had toppled regimes in both Iran and Guatemala. The Directors of the CIA, appointed by the President, take their loyalty to the President seriously, and often have performed tasks against their own better judgment at their bosses' behest.

In return for this loyalty, Kennedy often went out of his way to shield the CIA from unwelcome scrutiny. At a news conference in November 1963 (six weeks before his death), Kennedy responded to a question regarding the CIA. A newsperson had asked Kennedy if the CIA was conducting unauthorized activity in South Vietnam. Kennedy rose to its defense, saying:

I think that while the CIA may have made mistakes, as we all do, on different occasions, and has had many successes which may go unheralded, in my opinion in this case it is unfair to charge them as they have been charged. I think they have done a good job.

Robert Kennedy also knew where the buck stopped. In 1967, when the CIA was criticized for giving illegal financial support to the National Student Association, Bobby refused to let the CIA take the rap. He went on record as saying that the CIA policies were approved at the highest levels of presidential administrations. "If the policy was wrong," Bobby said, "it was not the product of the CIA but of each administration." When Kennedy family friend Jack Newfield tried to goad Bobby into criticizing the Agency, Bobby again rose to its defense, saying, "What you are not aware of is the role the CIA plays within the government. During the 1950's . . . many liberals found sanctuary in the CIA. So some of the best people in Washington, and around the country, began to collect there. One result of that was the CIA developed a very healthy view of Communism, especially compared to State and some other departments. So it is not so black and white as you think."

The Kennedy brothers, Bobby more than Jack, soon became smitten with the clandestine world the CIA inhabited. Author and intelligence expert John Ranelagh most accurately summarized the relationship. According to one CIA man with whom Ranelagh spoke, "Robert Kennedy, in his shirtsleeves, delved into the inner workings of the agency. In the end, he did not shake it up as his brother had wanted, but fell in love with the CIA and the concept of clandestine operation." Ranelagh added:

Jack Kennedy realized, as he told Clark Clifford -- an influential and trusted Kennedy advisor and Democratic power broker -- "I have to have the best possible intelligence," and soon reversed his decision to punish the CIA. Both brothers saw that alone of the agendas of government the CIA was willing to take action and had tried to do in Cuba what the President wanted. The Bay of Pigs failure meant that the agency would not resist tighter control. Rejection of the agency was not necessary: the windmill was now the Kennedys' to turn and direct. They were determined to make it work under their close direction.(2)

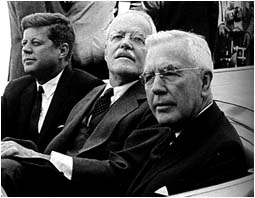

JFK with Allen Dulles and Dulles's successor, John McCone

It was Robert Kennedy who advised President Johnson to appoint Allen Dulles to the Warren Commission, along with CIA consultant and former World Bank Chairman John J. McCloy, once described by John F. Kennedy as "a diplomat and public servant, banker to the world, and Godfather to German freedom."(3)"I could never understand why Bobby tried to put some CIA people on the Warren Commission," LBJ later remarked. But as Gus Russo observes, the answer is fairly simple: "It would guarantee that Kennedy interests were served on the panel." As RFK told presidential advisor William Attwood, a heavy lid must be kept on the Commission's investigation, "for reasons of national security." But also for Kennedy security; as the CIA's commander, JFK had been actively involved in covert operations, moreso than the public was ever intended to learn.(4)

Prouty's claims about National Security Action memos 55, 56, and 57 are likewise the result of a limited and jaundiced perspective. Nowhere in these documents (or anywhere else) did JFK seek to remove the CIA from covert operations. They provide for a greater degree of input from the Joint Chiefs of Staff, whose advice the President apparently felt had been gravely insufficient for the Bay of Pigs operation; and advise that larger covert operations of a military nature be supervised by the military.

Military researcher Dave Fuhrman writes:

What Kennedy clearly wanted was for the military to provide advice and input, and for paramilitary operations which were too large to be "deniable" or which required substantial activities of a normally military nature to be handled by the military -- and that is exactly what happened under Operation Switchback in Vietnam. But Kennedy still saw the utility of the CIA and the value of covert operations and activities, and had no intention of making the Pentagon responsible for handling such programs -- although Mr. Prouty no doubt thought it should be that way.(5)

Thanks to Dave Fuhrmann, Clark Wilkins, and Bill Langston for their input.

You may wish to see . . .

The JFK 100: The Mystery Man, "X"

NOTES:1. Oliver Stone and Zachary Sklar, JFK: The Book of the Film (New York: Applause, 1992), pp. 106-11. All quotations are from the shooting script and may vary slightly from the finished motion picture.

2. Gus Russo, Live by the Sword (Baltimore: Bancroft, 1998), pp. 31-36.

3. Gus Russo, Live by the Sword (Baltimore: Bancroft, 1998), pp. 362-63.

4. Gus Russo, Live by the Sword (Baltimore: Bancroft, 1998), p. 363. While flawed in some other respects, Russo's book is an excellent source of information on JFK's involvement with covert ops.

5. Dave Fuhrmann, newsgroup post of July 31, 2001.

The JFK 100: The Mystery Man, "X"